We talk so much about ADHD nowadays that we might think for a moment that it has existed across all times. Although the symptoms we know so well were certainly shared by people since the early days of civilization, the identification of the traits and scientific observation is relatively new in history.

In Ancient Greece, records indicate that Hippocrates, the father of modern medicine, had already observed patients exhibiting symptoms of ADHD, but further developments happened only after the the 18th century. Sir Alexander Crichton, a Scottish doctor from Edinburgh, noticed in 1798 that some people were easily distracted and unable to focus on their activities in the way others could, motivating him to publish "On Attention and its Diseases." In this work, he described a condition characterized by an inability to maintain sustained attention on any object, accompanied by constant motor restlessness.

“Boy Studying”, oil and canvas by Ricard Canals (1876-1931) - Museu Nacional D'Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain

He termed this condition "Mental Restlessness," which closely resembles the modern description of ADHD.

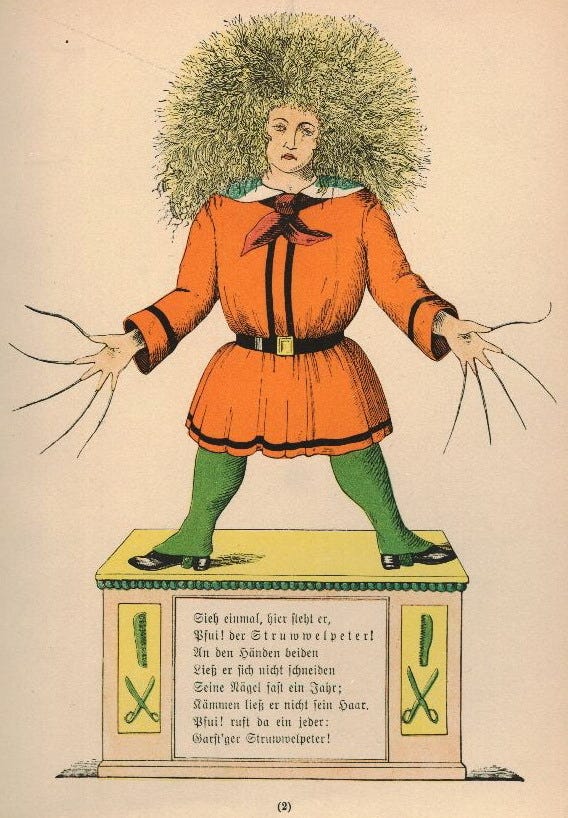

Later, in 1844, an allusion to ADHD-like manifestations was also identified in the writings of German physician Heinrich Hoffmann. He authored a series of illustrated stories describing the impulsive and inattentive behavior of a child named "Phil, the Fidgety" (Struwwelpeter), based on observations of his own son. While Hoffmann's approach was not clinical, the story of Fidgety Phil (pictured below) is often used as an allegory for ADHD.

After a century of inconclusive studies in the field, it was only around 1950 that the medical community placed particular emphasis on symptoms of impulsivity and hyperactivity over cognitive manifestations. This new approach originated the term "hyperkinetic syndrome," characterized by noticeable motor activity that made it difficult for children to remain still for even a second.

The influence of behavioral perspectives in the 1960s, notably through the work of authors like Stella Chess, led to the condition being called "hyperactive child syndrome." Finally, in 1968, this condition was included in the second edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-II (APA, 1968), under the name "hyperkinetic reaction of childhood."

In the 1980s, the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders established that hyperactivity was not a differential diagnostic criterion for the disorder, leading to the term "Attention Deficit Disorder" (ADD). It indicated that the disorder could present in two types: with hyperactivity and without hyperactivity.

The publication of the DSM-III (third edition) in 1980 expanded the definition and established that hyperactivity was not a differential diagnostic criterion for the disorder, leading to the term "Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD)." It was further subdivided into two categories: ADD with and without hyperactivity. In 1987, the subtypes were removed, and the disorder became known as ADHD with the DSM-4.

From the 1990s to today, advancements in neuroscience, genetics, diagnostic imaging, and computational modeling have pioneered new knowledge, expanding the way we see, detect, and treat ADHD. The most recent diagnostic manual, DSM-5, incorporated significant changes in how ADHD is understood.

ADHD was now included in the division of neurodevelopmental disorders, along with others like Autism Spectrum Disorder. Additionally, for the first time, the diagnostic criteria recognized that this condition is not exclusively a childhood disorder but can persist into adolescence and adulthood. It is also differentiated into mild, moderate, and severe levels.

Cases began to climb significantly since the 1990s. This may be partly due to doctors being able to diagnose the condition more readily, as well as increased awareness of the condition, in part helped by famous people making public statements about their own diagnosis of ADHD.

The experiences of celebrities such as Simone Biles, Johnny Depp, Emma Watson, and Michael Phelps are likely to have reduced the stigma and led to a demand for many adults and children to be tested for the condition. This may have fueled the increase in diagnoses and suspected cases compared to periods in the past.

In conclusion, we can consider ourselves privileged to live in a period of history where our problems related to executive functions, focus, capacity to concentrate, organization, planning, and control can be medically addressed and treated. But there's still a lot of challenges, taboos, and prejudices to overcome: we are still living in a world where the neurotypical view is dominant, so there's a long way to go for us.

Understanding the long journey of centuries until science and society finally recognized ADHD is a signal for all of us that everything has a time to happen if it's really true, and our time is this very moment! We can do anything, anywhere, at any time.